Misery Loves Company

When it was published, reviewers said ‘Jeez, that’s one messed-up book’ (I’m paraphrasing there).

It was the first adult classic I read. I was about twelve and didn’t understand large chunks of it, but have re-read it many times since, and it’s one my most loved books, ever.

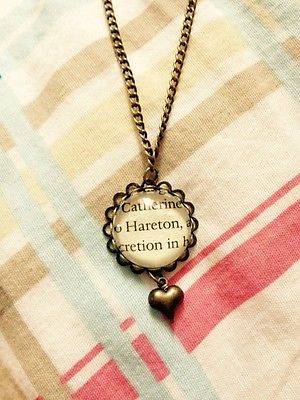

I have a Brontë shopping bag. A Wuthering Heights necklace made from a page of the book that features my favourite character’s name. Essentially, I am a bit of a Wuthering fangirl. But, that doesn’t mean I can’t see its faults. The narrative is a little confused at times, not all of the voices are substantially different when they take of over the reins, but as the reviewer from the Examiner said in 1848 –

If this book be, as we apprehend it is, the first work of the author, we hope that he will produce a second,—giving himself more time in its composition than in the present case, developing his incidents more carefully

It was indeed Emily’s first book. And paper costing what it did, countless drafts were not easy to accomplish, especially when every word is written and re-written by hand.

Some reviewers were just damned harsh. The North British Review said in 1847 –

Here all the faults of Jane Eyre are magnified a thousand fold, and the only consolation which we have in reflecting upon it is that it will never be generally read.

Some reviews were found in Emily’s desk when she died, that was not one of them. And I don’t blame her. Ouch.

Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper sums it up for me, saying in 1848 –

Wuthering Heights is a strange sort of book,—baffling all regular criticism; yet, it is impossible to begin and not finish it; and quite as impossible to lay it aside afterwards and say nothing about it.

Wuthering Heights taught the adolescent, and adult me, the following things –

* No matter how dire things seem, and how impossible an escape from an awful situation with an awful, bitter, nasty person, chin up, they could just die. Heathcliffe wasn’t old, or in poor health, but he pretty much just decided to die, over the course of a few days, he just left life. Anything can happen. Nothing is permanent.

*In some parts of the world, if cousins didn’t marry, humans would be endangered. When reading the book, it’s weird that many of these relationships are between cousins, but there’s not a whole lot of other people about. Everyone should have been glad old Earnshaw brought Heathcliff back from Liverpool, otherwise there would have been even fewer genes in the pool, and even more extra digits and folk with eyes too wide apart. Although, I was born with 12 fingers and 11 toes, and my parents are not from the same place at all, so please don’t brand all of us blessed with excess digits as inbred. Just some.

I loved the book as it was strange. It suited me as a strange teen. I also ended up moving to the area in my late teens/early twenties, and had my daughter there. I picked her name from a stone in Bradford’s Undercliffe Cemetery. It’s somewhere I love and could easily move back to. Living twenty minutes from the Brontë Parsonage, and being in possession of a visitor’s season ticket, on any rainy afternoon I wanted, I could wander about the churchyard, pop in and see the couch Emily coughed her last on, have a cup of tea and bun in a cafe before heading home, and that was a first class day out for me. And it has always annoyed me immensely when people refer to it as a romantic novel in which Heathcliff is some kind of hero. Him, and his story, are brutal. He’s flawed and occasionally human, but generally, detestable.

The use of the imagery of a pack of dogs about the house, fighting and being kicked, presents the most discomfort to me, especially as a teen I had to break up a few dogfights myself. At the time they felt like a metaphor for the whole novel to me, the way dogs fight with 100% of themselves, with no reserve, and how disturbing raw, desperate animal noises can be. I also found the use of corpses, especially when Heathcliff digs Cathy up, and then later, gets the sexton to leave him alone with Cathy in 18 years time when the grave is opened again for Edgar, illustrates how less creepy they found the human corpse back then, as death itself would have been so normal. The graveyard in front of the Parsonage was so overcrowded that human fat and skin would rise to the surface in certain weather conditions, and people would slip over. It’s very likely the Brontë family all took a spill at one time or another due to excessive rising corpse-fat, on their way into church. But bodies, in spite of being more common, were more sacred then, and Heathcliff’s invasion of the grave would have disturbed readers far more than they do us. Not just for superstitious reasons, but that would have been part of it. Disturbing the dead was really not on.

It was also the first thing that came into my head when, upon being about to embalm a woman in her 50s, who had died suddenly (it’s my job, not a weird invasive hobby), I was told her husband would be present. This presented a real concern, as I had to put up a sheet, as for him to see the whole process could have upset him further, so left him just her lower legs and feet for the bulk of the time. He sat on a chair at the end of the table, holding one foot with one hand, and resting his cheek on the other.

Her cold, lifeless feet.

And Heathcliff helped me understand his attachment.

What a brilliant piece! That’s given me a totally fresh perspective on a much-loved book. Embalmer’s literary theory should definitely be a thing – you should get on to that – although I fear the nightmarish image of human skin and fat rising in rain-drenched graveyards has just knocked zombie apocalypses off the top spot of my ‘things most likely to cause insomnia’ list. So, yeah, thanks for that! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Run! It’s the ghost of Anne Brontë! | Hard Book Habit

Pingback: Cheer Up Dave, the dead are still asleep. | Hard Book Habit

Pingback: “Sensible, but not at all handsome” – ‘Jane Eyre’ revisited | Hard Book Habit

Pingback: Lighten up, Charlotte. | Hard Book Habit

Pingback: You and I both know it’s time for a Muppet ‘Wuthering Heights’ | Hard Book Habit